What COULD the Soviet Lunar program have achieved?

What's the simplest "alternate history" route to success?

When considering the Soviet crewed Lunar program, I tend to flip between two views.

That it was doomed from the start, (Insufficient and irregular funding, unreasonable time scales, poor quality control, lack of political support).

That major success was narrowly missed.

The second view needs justification, so what do I mean?

Beating Apollo 8 in getting a crew to the Moon without landing was very achievable. Vasily Mishin is on record as saying that Korolev, had he lived, would have found a way to do this.

Beating Apollo 11 to a landing was never on the cards the way things developed.

Getting the N1 to operational status:

Could the N1 have reached operational status? My answer to that is yes.

When the program was cancelled, the N1-8L had been rolled out to the pad, and fuelled for testing. Hopes were high it would succeed, with good reason:

The N1-7L nearly reached orbit, problems were understood

The new engines were installed, and they could be fully tested before flight

The upper stages had proper test stand testing, and were considered reliable

Plus it had a MASSIVE increase in telemetry to refine the design.

The N1-9L was nearly complete, and scheduled for fly a few months later. The expectation of the engineers was that the N1 would be flight rated after the 9L flight.

So, to get an operational N1 would require a few extra months only, or being that much further ahead. Once flown to orbit, I find it difficult to see the rocket being cancelled.

The 6L had revealed insufficient roll control, and the 7L showed problems after the inner 6 engines of the first stage shut down. Could these issues have been identified earlier?

The big problem was the second flight, the N1-5L, which fell back onto the launch pad moments after lift-off. Alexei Leonov has said that’s when he knew he wouldn’t be the first man on the Moon.

The problem was diagnosed as something unwanted in the fuel lines, such as a loose bolt. I want to consider two alternate scenarios.

The N1-5L clears the pad, but still crashes shortly after launch, without destroying the pad.

The 5L test flight is more like the N1-6L, and reveals the roll control problem.

In the first case, I think the program would have been able to move forward faster than it did historically. No long and painful post mortem needed, and no distraction from fixing things for the next launch. If the project cancellation date does not move, this would provide time for the N1-8L and N1-9L to fly, and the N1 achieves flight status. The loose bolt feels very random, so having it happen later in the flight doesn’t seem a big ask.

The second case is much more interesting to me. If the N1-5L reveals the roll control issue, then the N1-6L flight seems likely to be more like the N1-7L - getting to the start of the first stage shutdown. Which means that the actual N1-7L would have a GREAT chance of reaching orbit.

Surely if an N1 had successfully reached orbit, cancellation would be highly unlikely?

Now, none of this would beat Apollo 11 to the lunar surface. But with a working heavy launcher, the extensive plans to outdo Apollo later would have had a fighting chance of happening.

L1 beating Apollo 8 to the Moon:

The L1 project, to get cosmonauts to the Moon without a landing, was an achievable goal. And the Soviets were hopeful of this, right up until Apollo 8 succeeded. The hardware was being flown to the Moon under the “Zond” program, (Zond meaning probe), to disguise it from being recognised as part of the crewed lunar program.

What went wrong?

The L1 program was given to Chelomei, who used the UR500 missile, (later Proton rocket), as the launcher.

It was a much easier goal, but the record of the Proton / UR500 was terrible in the early days. A rushed development program led to dozens of failures between 1965 and 1972. Proton did not complete its State Trials until 1977, at which point it was judged to have a higher than 90% reliability.

Think about that - 12 years to reach a 90% level of reliability. It’s worth pointing out that Chelomei’s alternative to the N1, the UR-700, was basically a bundle of Protons, and would have had much worse reliability.

While cosmonauts were willing to trust the escape system, the program managers were not - they were extremely concerned about what would happen if the crew were enveloped in clouds of toxic fuel after the escape system worked.

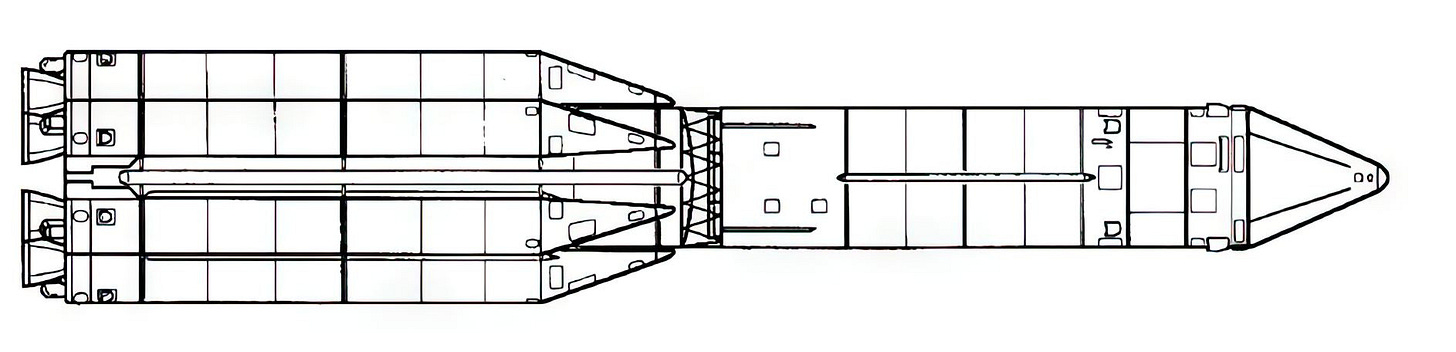

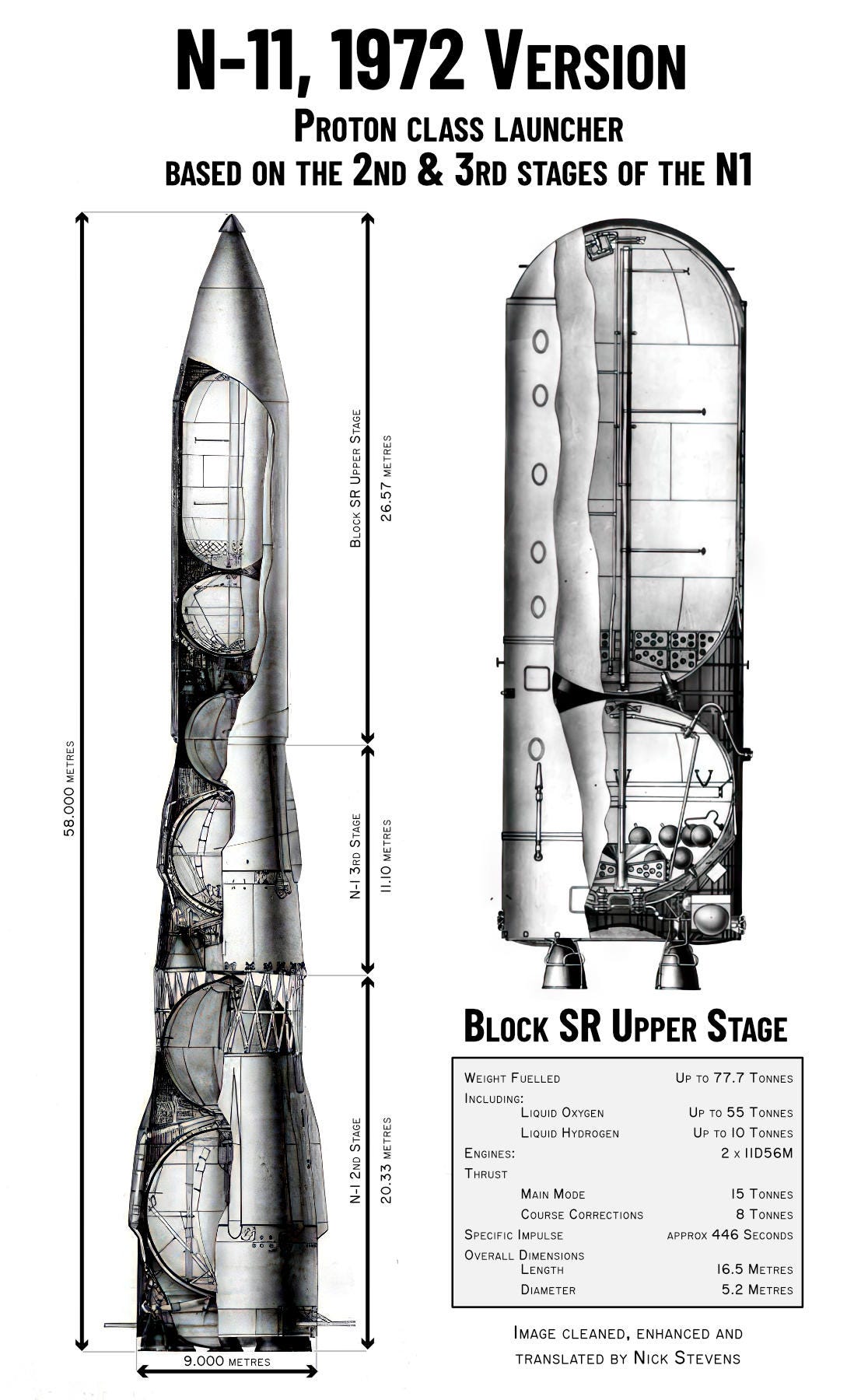

This was not the only option. Korolev’s proposal was the N-11, a largely forgotten offshoot of the N1 program.

It was a Proton class medium launcher, and was basically the N1 without the first stage. Boris Chertok in his biography considers not building the N-11 to be a very serious mistake. Here’s why:

All-up test stands were available for the second and third stages of the N1, those blocks could be tested to high reliability.

It would be N1 hardware and systems flying early, and enable them to be tested at a much lower cost.

This particularly applies to the engines.

There was even an attempt to revive the N-11 in 1972! Here’s a diagram I built of the proposal from that time.

Now, the obvious problem is that it’s still using the engines that caused so much trouble. But it’s a LOT easier to fly a few at a time than a full set of N1 first stage engines. So, while development would unlikely to have been smooth, it seems to me that it would have simplified things for the N1. And by starting flights earlier, more progress could reasonably be expected in the available time.

Perhaps the need for a filter to catch bolts in the fuel lines could have been identified, and prevented the explosion of the N1-5L?

And let’s not forget, “Better than the Proton” is NOT an ambitious goal. Even if it was no more reliable, escape from a rocket that doesn’t use such toxic propellants is MUCH safer.

So, where does this alternate path lead?

A replacement for the awful UR500/Proton, and a very good chance of beating Apollo 8 to the Moon.

Improved reliability, and MUCH earlier development / testing of key N1 systems

What’s not to like?

Extra Item!

Here’s video that’s new to me of the LK Lander being tested.

Here’s a translation of the Russian description.

For such tests in 1969, a full-scale experimental model E4098-222 of the lunar spacecraft was used. It was subjected to static loading with the help of special rods and levers with hydraulic drives; part of the tests involved complete destruction of the most critical structural elements.

Thus, the rods and sub-braces of landing supports, cockpit spandrels and power pylons of the frame were ruptured, with destructive stresses reaching 180% of the theoretical values of load-bearing capacity. In general, the ship's safety margin was close to the specified requirements and ensured the safety of the crew even under the most unfavourable landing conditions.

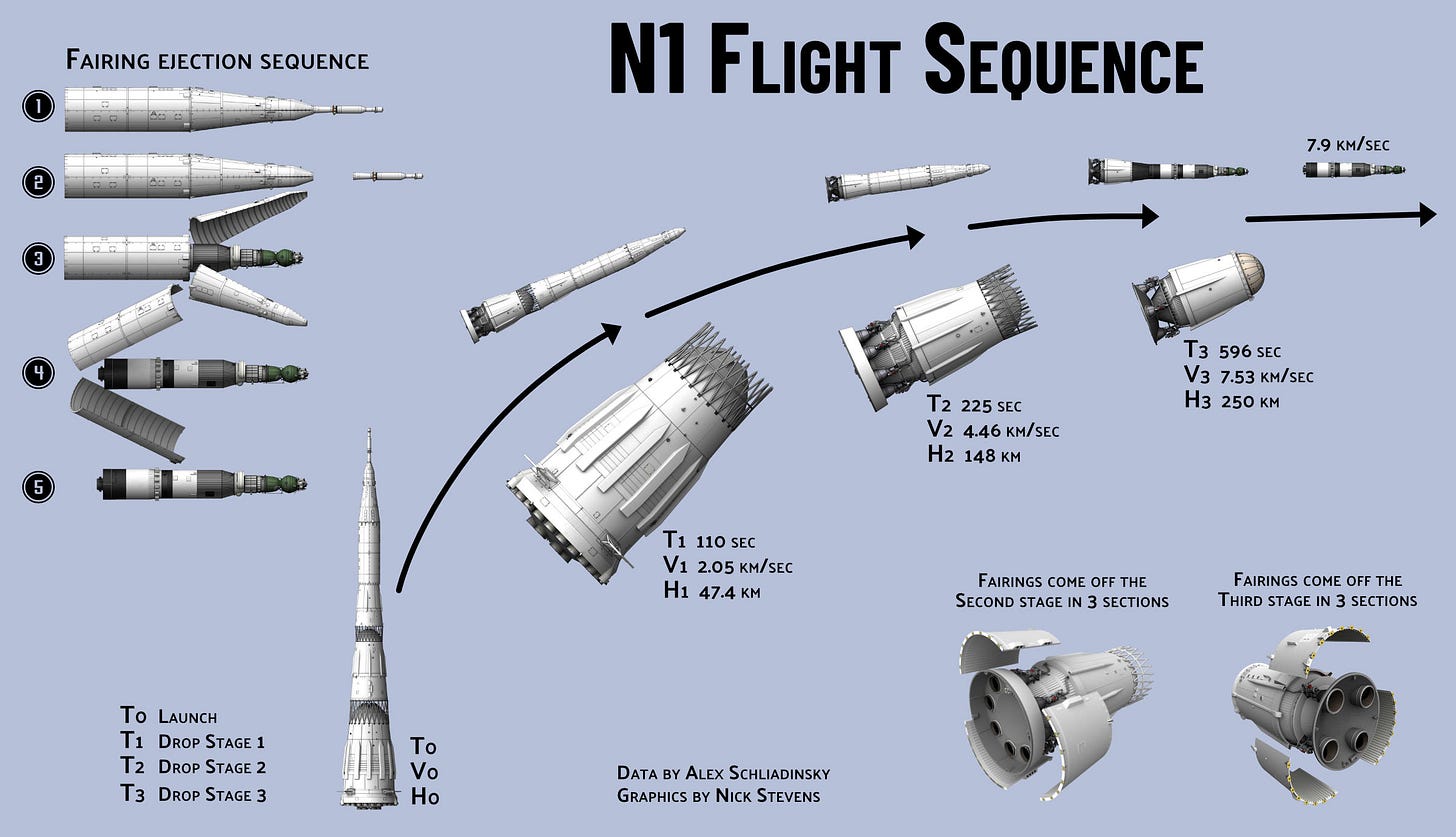

This edition’s cool Image:

I’ve been working on a rough sketch infographic by Alex, which dates back to the first edition of the N1 book. I decided to take the numbers, and redo the imagery, to make it more presentable. Please contact me if you wish to publish this infographic, the original is much higher resolution.

This edition’s cool link:

I must admit, I’m running low on cool Soviet Space links. If you have any suggestions, please leave them in the comments!

In the meantime, this is my Mastodon presence. (I bailed out of Twitter when Musk announced he would scrape it all, to train AI)

https://mastodon.art/@Nick_Stevens_graphics

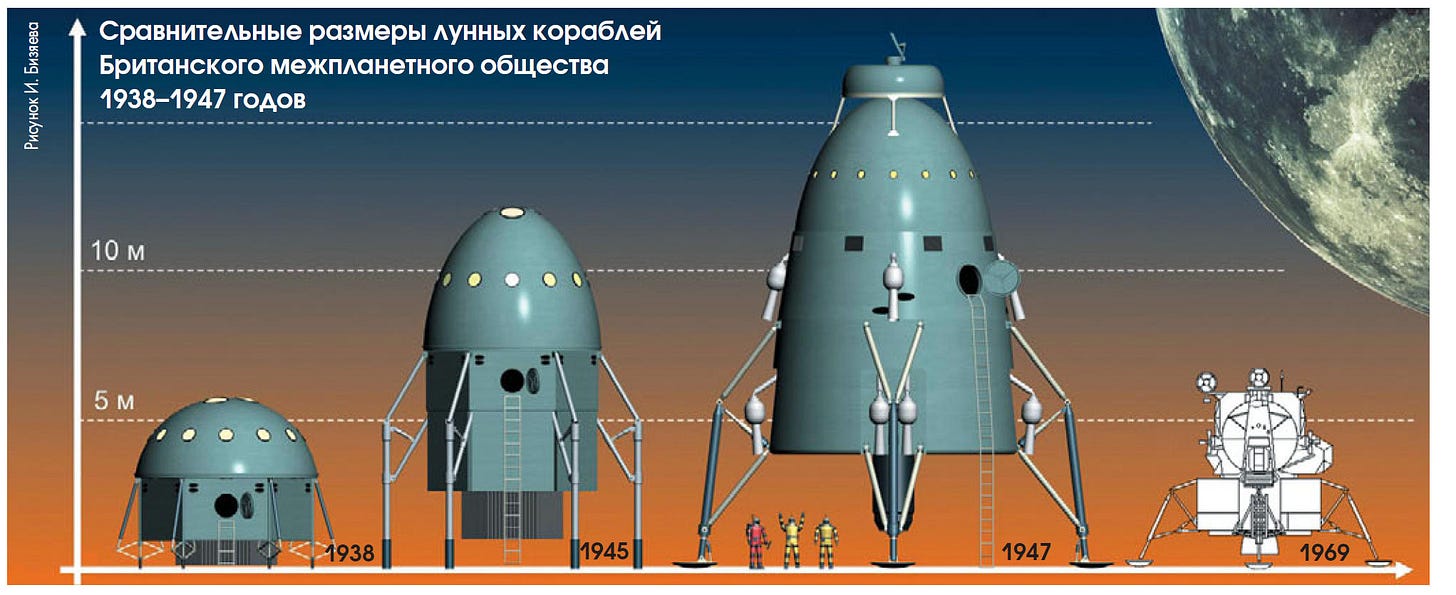

I tend to post quite a few obscure Soviet space images that don’t make it to the substack. Like this one:

This editions 7 day only download:

Novosti Kosmonavtiki, all 12 editions from 2009. The December magazine includes an article on the British Interplanetary Society’s plans for crewed lunar missions!

I agree with the bulk of this and particularly that they could have beaten 8 to a manned circumlunar mission. However, I think there are two crux issues this posts skips. One, ironically, the Soviets had competition in their program whereas NASA had a command monopoly. Two, and more to the technical points discussed here, the root failure was in Glushko and Korolev’s personal dispute and the resulting failure to develop a cryogenic hydrogen motor.

Absolute wonderful article Nick! One of your best ones so far, to be honest.