The N1 was not the only game in town when it came to crewed lunar missions, particularly at the start.

This substack post will briefly describe the competing launcher designs.

Yangel’s R-56

The generals of the Soviet Union had a saying: “Korolev works for TASS, (the state press agency), Chelomey works on crap, but Yangel works for us!” This really shows some of the tensions at play in the Soviet space program at the time. Korolev was always trying to get the military to back funding for his proposals, but they saw most of his work as having little, if any, military value. What would they do with a lunar base? Chelomey at this time had no significant space successes to his name, and his ideas were frequently wilder than Korolev’s. But Yangel was a missile man they trusted.

Yangel had previous experience with large space proposals though, and worked well with Glushko. Yangel’s proposal for a rocket was the R-56, and the preliminary design was published on 22nd May 1963.

R-56 performance requirements:

· Circular polar orbit, altitude of 200 km: 40 tonnes

· Geostationary orbit: 6 tonnes

· Orbiting the moon: 12 tonnes

· To Mars and Venus: 6-8 tonnes

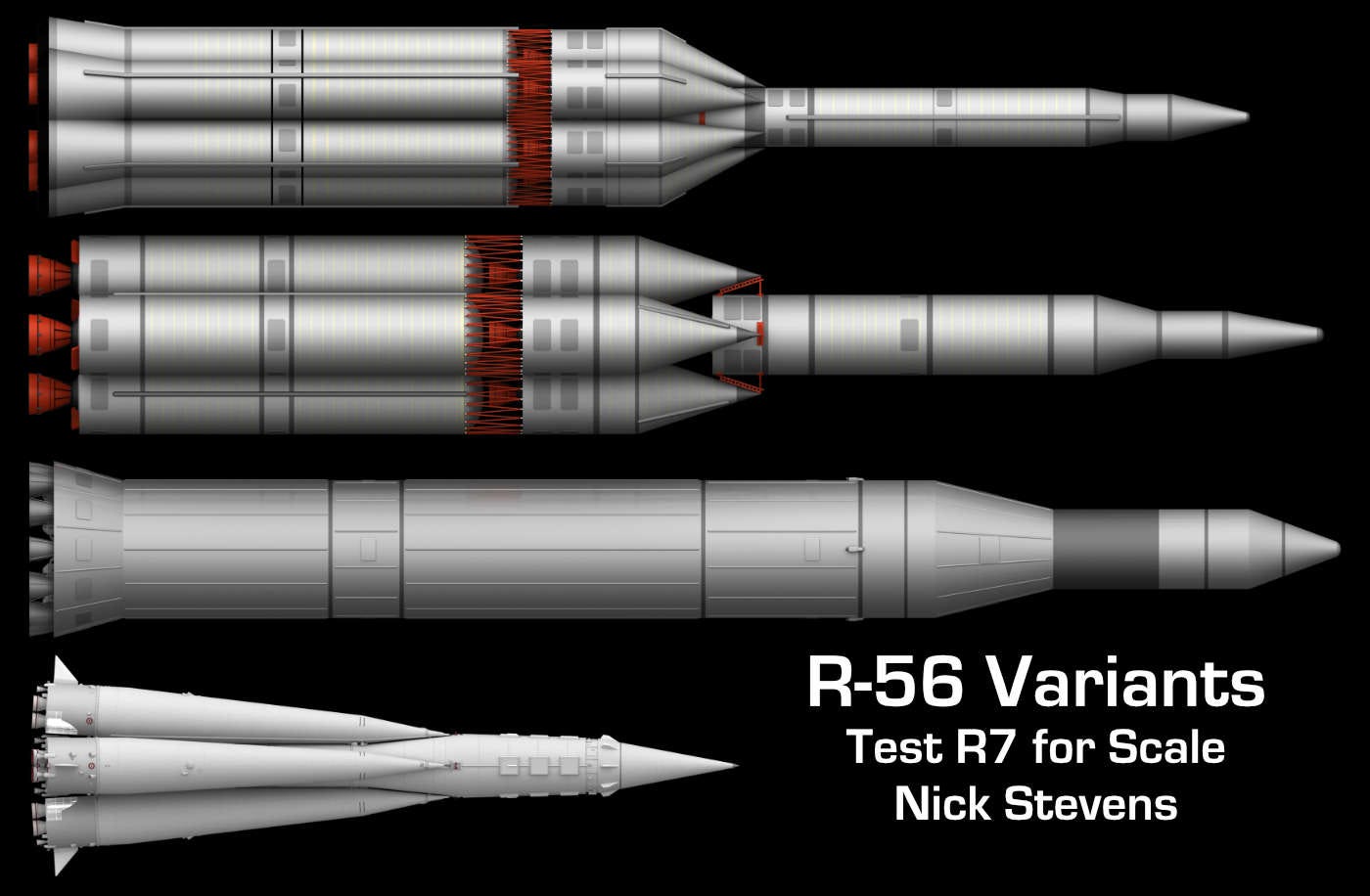

He suggested 3 different possible versions, based around the ease of moving sections around by rail. (This constraint on Soviet rockets is seldom acknowledged, they were generally manufactured a long way from the launch site.)

• Four-block with block body diameter of 3.8 m (close to the maximum possible for transportation by railway).

• Seven-block with body diameter of each block 3 m (the most manufacturing experience).

• Monoblock with hull diameter of 6.5 m, fully assembled in the factory, transported by water.

The multi-block versions are particularly notable for having boosters with 2 stages, as seen in this photograph.

Studies showed that, despite the difficulties of transport, the monoblock scheme has clear advantages compared with other options. This was therefore the preferred proposal.

Chelomei’s Universal Rocket Family

This is probably the best known N1 competitor, particularly the UR-700 which would be powerful enough for direct ascent and return missions. The smaller UR-500 design was built, and became better known as the Proton, still in service until recent years.

Diagram of the Proton variants, credit: Asif Siddiqi and Peter Gorin.

Right up until the Apollo 8 flight around the Moon, the Soviet Union was still hopeful of at least beating the USA to reach the Moon, even if they did not land. Test flights were made using a UR-500 (8K82K), with an escape system, and animals on board.

Аlexey Leonov said later that a group of cosmonauts addressed a letter to the Central Committee, with a request to allow a flight on the 7K-L1 spacecraft. This despite the launchers poor reliability, but simply "to take the risk". Chief designer V.P. Mishin was opposed to this.

Mishin felt that the unsuccessful launches of the Proton forced management to think seriously about the fate of the crew. Even if the emergency escape system took the crew to a safety, they could still be overtaken by a toxic cloud of the highly corrosive propellants used by Chelomey and Glushko. Therefore the lives of the crew could not be trusted to this unreliable rocket. In the end it was tortoises, not cosmonauts that flew around the Moon on a Proton-launched Zond.

The L1 program, to me, is key evidence that Chelomey’s proposal would not have fixed anything – he had his chance, but failed to deliver the much simpler L1 mission.

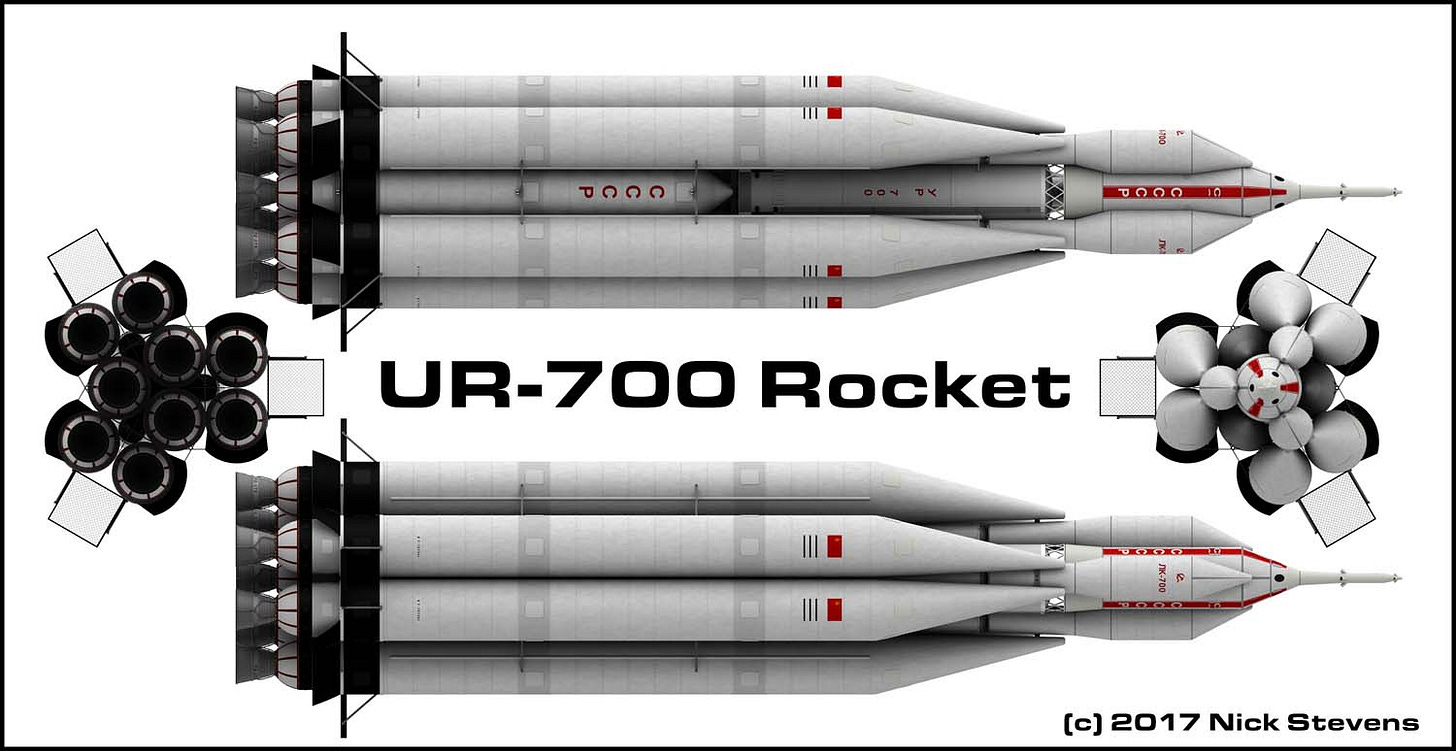

The UR-700 was the direct competitor for the N1 role, and it was a VERY ambitious concept. It was powerful enough for a direct ascent to the Moon, and direct return – no risky orbital rendezvous to accomplish. It was a late arrival though, presented to the L3 project commission headed by M.V. Keldysh on November 17th 1966, as an alternative to the N1-L3 project.

6 boosters on the sides were in pairs, and they also pumped fuel into the core stage, so the core was still fully fuelled when the boosters were discarded. The length of UR-700 together with LK-700 lunar craft would be about 75 m. Launch mass was about 4500-5000 tonnes.

Some large scale models were built to test the movement of the fuel:

The UR-700 launcher / LK-700 lander complex was designed not only for one-time landings on the Moon, but also for creation of long-term crewed bases. Construction of the base was planned in three stages:

The first launch would deliver a heavy, unmanned, stationary lunar base to the surface of the Moon.

The second launch would deliver a crew to the Moon in the LC-700 spacecraft, with the base being used as a beacon. Once the ship has landed, the crew move to a fixed base and the ship is conserved until the return flight.

The third launch delivered a heavy lunar rover to the Moon, on which the crew was to make expeditions across the lunar surface.

Nuclear R7 / Soyuz

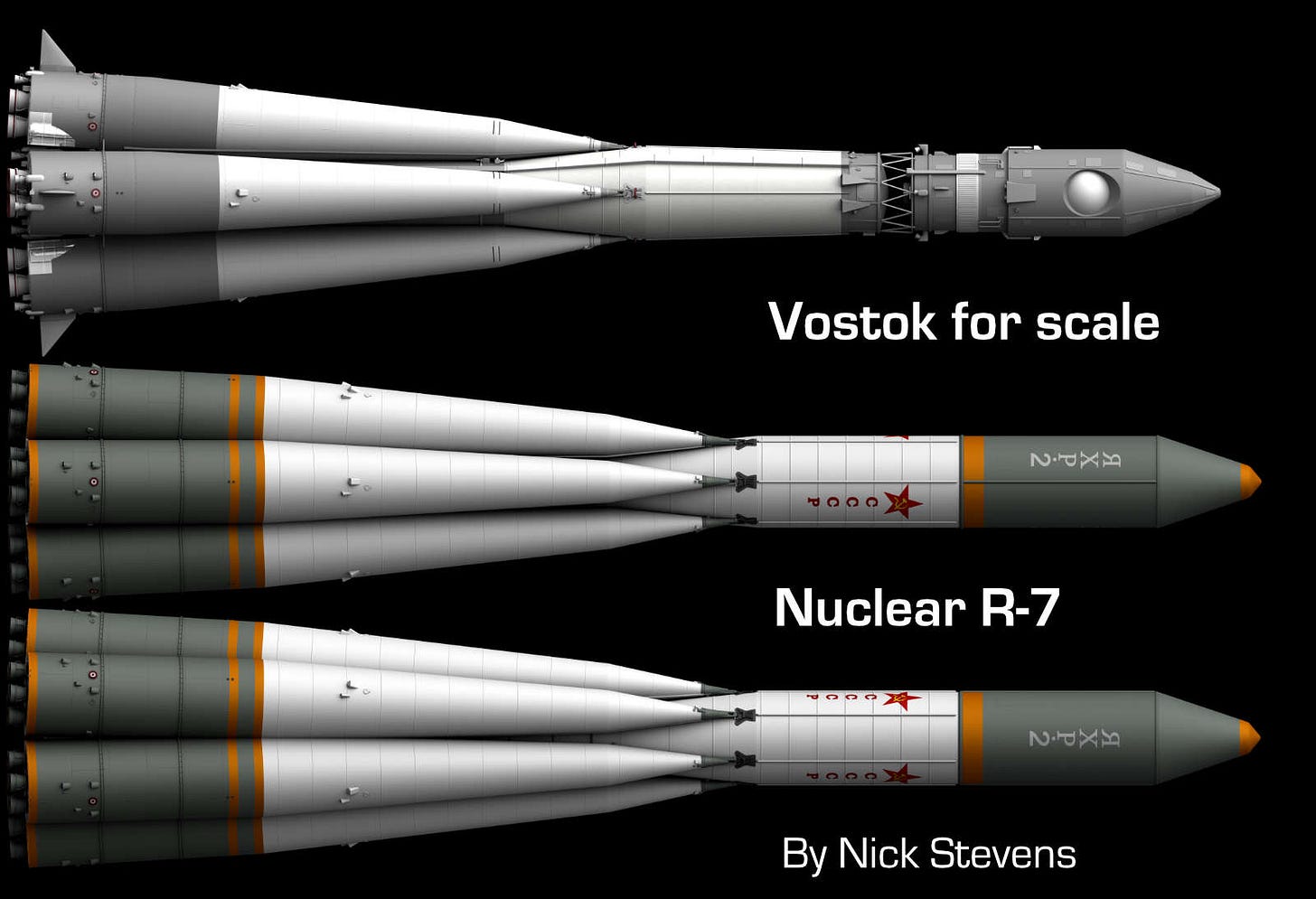

Preliminary designs for rockets with nuclear propulsion were approved by Korolev on 30 December 1959. Nuclear rocket engines provided a tangible advantage when it came to large masses. Launch vehicles with an initial mass of 880 to 2000 tonnes were able to launch 40 and 150 tonnes into the near-Earth orbit.

Korolev had a proposal to upgrade the R7 / Soyuz launcher with a nuclear second stage. This would involve lengthening the core stage and boosters, and upgrading from 4 to 6 boosters. The core stage was the nuclear element, and it would not start until lifted above the atmosphere. The boosters would each use six oxygen-kerosene engines, designed by N.D. Kuznetsov. The launch mass of this rocket ranged from 850 to 880 tonnes, and payload put into orbit – between 35 to 40 tonnes. (Compared with about 5 tonnes for the Vostok R7).

I have an old blog post on this rocket here:

http://nick-stevens.com/2017/06/17/rn-2-nuclear-r7-historical-reference-information/

The nuclear engine was designed by the Khimavtomatika design bureau. The RD-0410 engine was the first and only Soviet nuclear-powered rocket engine, but it was never flown.

Decisions.

The initial requirement, to ensure absolute superiority over the USA, was to put 200 tonnes into Earth orbit. With the original N1 design, that would need 3 launches. With the UR-500 it would need no less than 20 launches, and even more for an R-56 based mission.

The development of nuclear engine technology was considered high risk, particularly as the payload capacity achieved was within the range of conventional rockets, so this proposal too was rejected.

The UR-700 was not even on paper at this stage, so it was not considered.

______________________________________________________________

Cool image of the week!

UR-700 plans, signed by Chelomey!

Cool Link of the Week!

International Association of Astronomical Artists, gallery of space art.

Work by the best space artists in the world.

That’s all folks!

Just a comment that diagram of the Proton variants should be credited to Asif Siddiqi and Peter Gorin. Those drawings were done by the Peter (who tragically passed away) and commissioned for my book Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945-1974 (NASA, 2000). Unfortunately, they were mistakenly put online by NASA without my permission. (Lost cause when things are put online!). Best wishes, Asif

Возможно, будет интересно в качестве дополнения: УР-700. Лунная ракета Челомея.

ч.1: https://youtu.be/7DoIEPBkOmU

ч.2: https://youtu.be/8ZT5PzArVdI